BEYOND-HUMAN VOICES: BERLINALE 2024

- Marina Drozdova

- Mar 4, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 10, 2024

The main prizes of the Berlinale 2024, perhaps more than ever, reflected the extreme points of possibilities of cinematic genres at the moment. Here is an unyielding political debate about colonialism (“Dahomey”, Mati Diop), a mannerist clownery about the ends and beginnings of Time (“The Empire”, Bruno Dumont), a magical comedy-essay on the nurturing of faded feelings (“A Traveler’s Needs”, Hong Sangsoo), and a narco-thriller starring a talking hippopotamus (“Pepe”, Nelson Carlos De Los Santos Arias). A splendid outcome of two-week vigils in the dark of cinemas — the analysts as well as ordinary viewers have agreed.

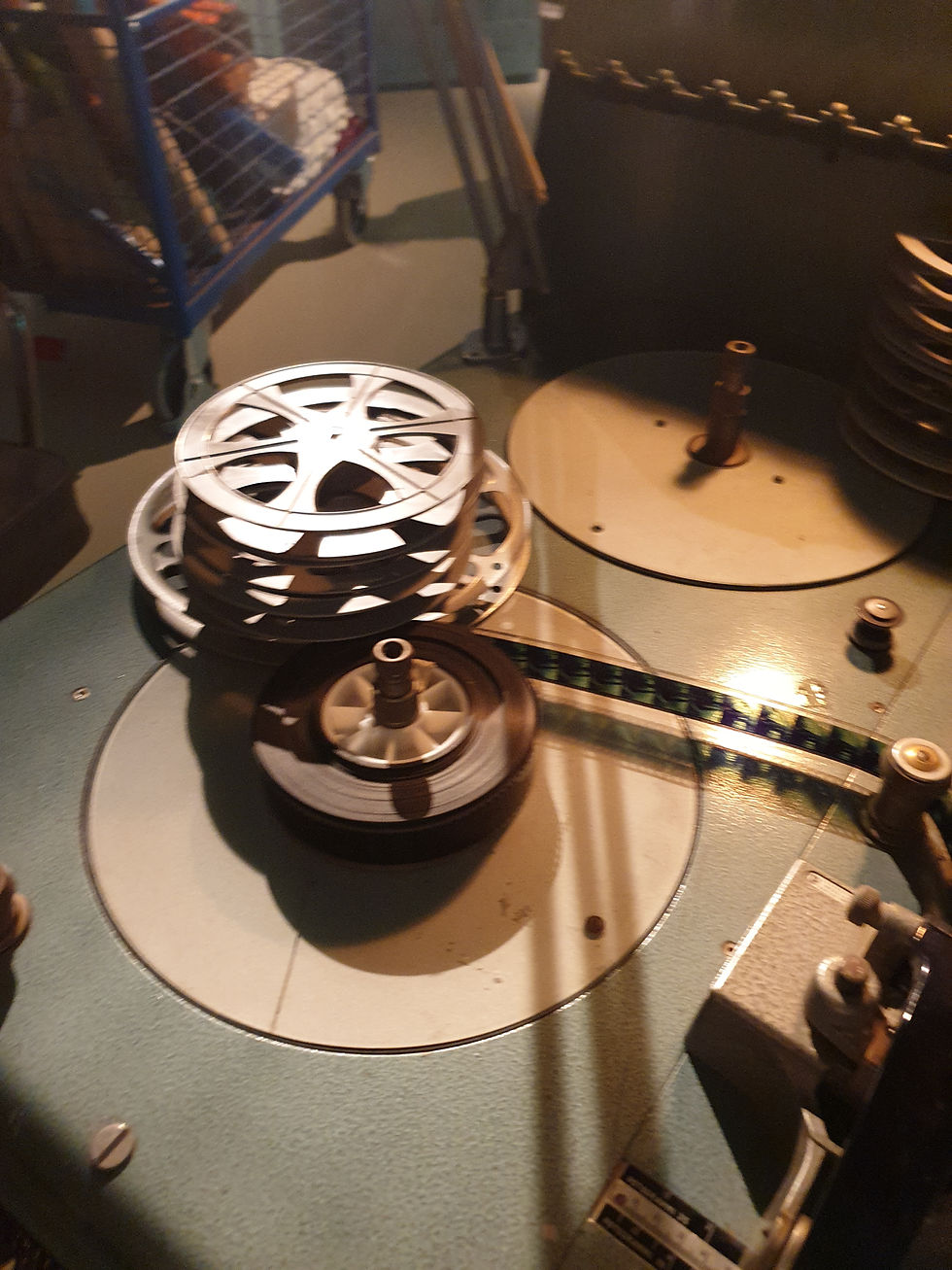

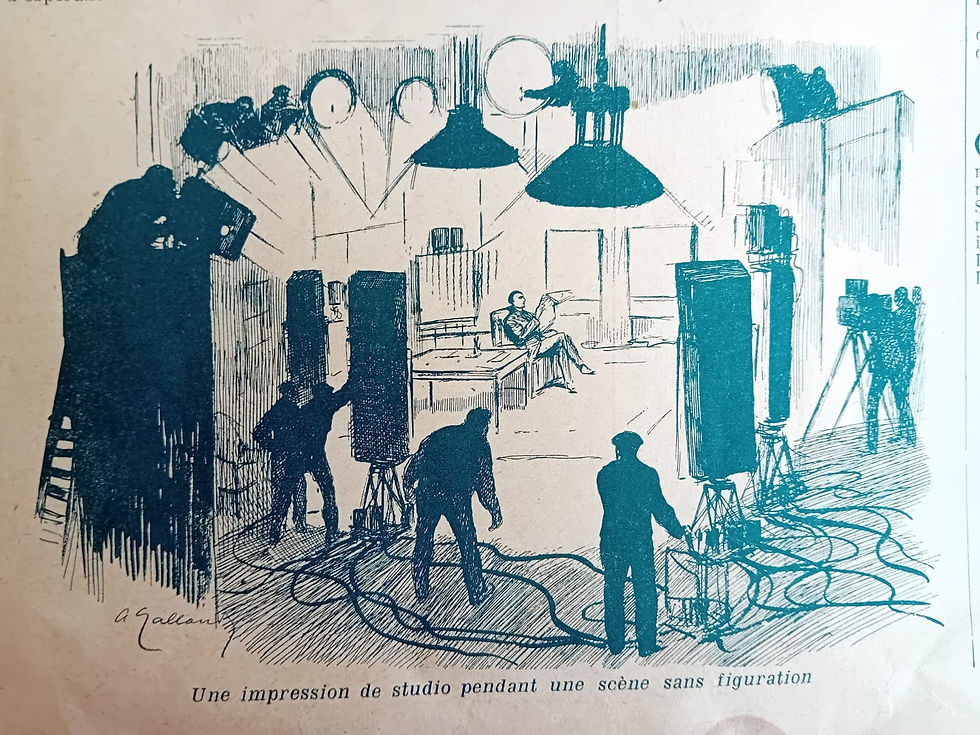

Albeit the term “ordinary viewers” betrays a bit of shortsighted arrogance, especially in Berlin, where — over many decades — the Berlinale has created an extraordinary audience that understands the finer points of cinematography… and would even brave the cold of sleeping on the ground, waiting in long lines for tickets: oops, that’s almost a thing of the past — now the tickets are purchased online... But nonetheless, the dedication of the audience persists. Note that this year, even more than before, the Berlinale has spread its screenings across different parts of the city, and this kaleidoscope of cinemas and screenings fascinates and captivates a true cinephile.

There is a common misconception that politics drives the Berlinale when creating its competition program and handing out prizes. Rather, for decades, the festival has broadly focused on anthropology. And currently, the spectrum of key prizes is amazing — it so accurately captures the crisis of the human factor. Modernity has upended an age-old riddle: a car accident happens, the father is no good, the son is brought to the operating room, the surgeon comes in and says, “I can’t operate, this is my son”. Question: how could this happen? The old-fashioned answer: the surgeon is the mother. The modern answer: they are in alternative realities. Likewise spanning reality’s different dimensions, in the Berlinale’s prize-winning films, sculptures come to life, a hippopotamus speaks, aliens party at a village bar. Only Isabelle Huppert continues to play games of shimmering realism — despite the fact that she is definitely from another planet or she’s a meteorite fragment come alive!

“A Traveler’s Needs” by Hong Sangsoo received the Silver Bear Grand Jury Prize: Upon accepting the award, the director musingly queried the jury what they had seen in his small film to crown it so grandly. Oh, the modesty of great talent. Hong Sangsoo is known for his transparent, scintillating, minimalist micro-dramas — the action always seemingly takes place inside Matisse’s aquariums, where pensive sleepy little fish circle about their endless errands. Hong Sangsoo’s true cinematic genius on screen is a reminder of the essence of cinema art. In the leading role, Isabelle Huppert plays a dubious French teacher in Seoul. We couldn’t fathom what warm winds had blown her into Seoul. Incongruous yet extremely organized, she decides to earn money for her tourist needs by giving lessons. Her lessons are mini psychoanalytical etudes performed with her students — prompting the students to first remember emotions, and subsequently — through emotions — words and verbs. The entire narrative is a hypnosis session. Sitting on a bench in a park the melancholic heroine (Isabelle Huppert) plays a flute, and the sounds fly aroung her like invisible microscopic birds. She herself is carried by some wind from France to South Korea. In order to earn money for dailylife she gives lessons of French Language, but these are strange lessons: she teaches in English, and her idea is to excavate deeply hidden emotions of “students”, made them formulate then and afterwards to translate the these sentences into French. The method will help people to remember words in foreign language. Probably, she’s right. As always in the films of this director – but, yes, especially in this film - it's just a pure, inevitable and somehow indifferent "cinegénie". Impressionism and minimalism with an unbelievably clear display of hidden emotions - the director masterfully plucks invisible strings. Just a few directors are capable of that - thus it's pure art, but of course we could add the stories about cyphes and etc. Huppert is mockingly Hitchcockian. Caricature vignette of her infernal images Finally - focus...

Bruno Dumont won the Silver Bear Jury Prize for “The Empire.” He wasn’t one to ask, “for what?” He knows — for utter eccentricity. The film is a parody of science fiction and, simultaneously, of medieval knightly novels — a circus clownery about aliens and the police. Top caliber absurdity. Fabrice Luchini is superb. Fans of “P’tit Quinquin” would handcuff themselves to the cinema seats so as never to leave. Sci-fi parody & mockery.

So, here the cosmic forces are constantly mimicking into people. And therefore, the locals are not fishermen, farmers and drunks (not at all…) - but alien groups who call each other “ones” and “zeros”.

The architecture of the film (and the architecture in the film) is unbelievably funny. And this whole ideological gag is about the conflict of everything secular and jovial with everything that is obsessed with the principles of morality and punishment.

The ideological differences between cosmic “zeros” and “ones” become meaningless when human flesh asserts itself. Apocalyptic burlesque laughter.

And yet, the little interstellar interludes are irresistibly acted out by policemen Carpentier and Van der Weyden.

Cottin and Luchini are brilliantly beautiful in all the nuances. They take human shape by invading the bodies of the town’s mayor and a hapless tourist guide. Luchini in a Pierrot-like costume is a real King of nonsense in deadpan seriousness. He is the magician of of humour.

“Dahomey” by Mati Diop received the Golden Bear for Best Film: the main prize. This documentary discourse about postcolonial traumas unfolds against the backdrop of the return of the royal treasures of Benin (formerly the Kingdom of Dahomey), appropriated by France. The film represents contemporary political art — and should be perceived as such. Pictorial and semantic collages denote ideas devoid of emotions. The wooden sculpture of the King of Dahomey speaks with a human voice. The white hands of French museum workers — consider them colonialists — carefully pack the artifacts for homeward-bound shipment. Of the seven thousand items removed, only 26 are returned. And this insane difference in numbers originates student discussions — the camera moves from the museum storage to the university auditorium. The genre is a documentary fable.

The protagonist of the film “Pepe” (Silver Bear for Best Director) is a hippopotamus named Pepe, born on the estate of the drug lord, Pablo Escobar. The tragic figure of the animal, weighing several tons, becomes an unexpectedly massive metaphor in this film by the Dominican director. Either this is a reincarnation of Escobar… or an anticolonial symbol. The director wants to see the world through a behemoth’s eyes, and who would dare stop him. Escobar brought three hippos to Colombia in 1981. He collected a whole zoo of exotic pets; most did not survive, but the hippos adapted to South America’s rivers. The director learned the story of the struggle between the young hippo, Pepe, and the alpha male, Pablito, from a local artist, Camilo Restrepo. Pepe lost and had to leave the herd. The locals decided that Pepe was a water monster. Thus began the hunt for Pepe. References to “Moby Dick” and “The Old Man and the Sea” create another metaphorical dimension of the director’s imagination. And the screen blossoms with the colors of the tropics — orange, emerald, lilac. The story contains references to Moby Dick and Hamingway' «The Old Man and the Sea». But the angle is completely different: we see the world through Pepe’s eyes. Pepe philosophizes, and what he says is deeply political. The last time we saw speaking animal – it was the tiger in Apichatpong Weerasethakul film. The director of Pepe doesn't have the ability of mesmorizing as Weerasethakul, but with the help of a hippopotamus he tries to unravel the essence of lonely monsters.

The Berlinale Main Competition featured the world premiere of “Architecton” by Victor Kossakovsky. As usual, this documentary visionary created something amazing: his characters are stones that sleep in the sun, sometimes stir, or turn into a stone storm. Shattered cities. Abandoned houses. Dust. Tragic mannerism. The cameraman did a brilliant job. And the director continued to wonder whether civilization was perishing before his eyes — something that has concerned him for some thirty years.

“Architecton” echoes another landscape of eternity immortalized in stone and spirit — more than a hundred years ago, Chekhov wrote in “The Seagull” of all men and beasts:

“People, lions, eagles and partridges, horned deer, geese, spiders, silent fish living in the water, starfish, and those that could not be seen by the eye, — in a word, all lives, all lives, all lives… The bodies of all living creatures have turned to dust, and the eternal matter has transformed them into stones, water, and clouds; but their spirits have merged into one — and that soul of the world am I! In me are the spirits of Alexander the Great, Caesar, Shakespeare, and Napoleon, and the least of the leeches. In me, the consciousness of man has merged with the animal instinct; and I remember everything and everyone, every life; and every life I live anew.”

The leeches are especially delightful here...

Comments