LIBERATORS OF SHADOWS

- Marina Drozdova

- Nov 26, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Nov 29, 2025

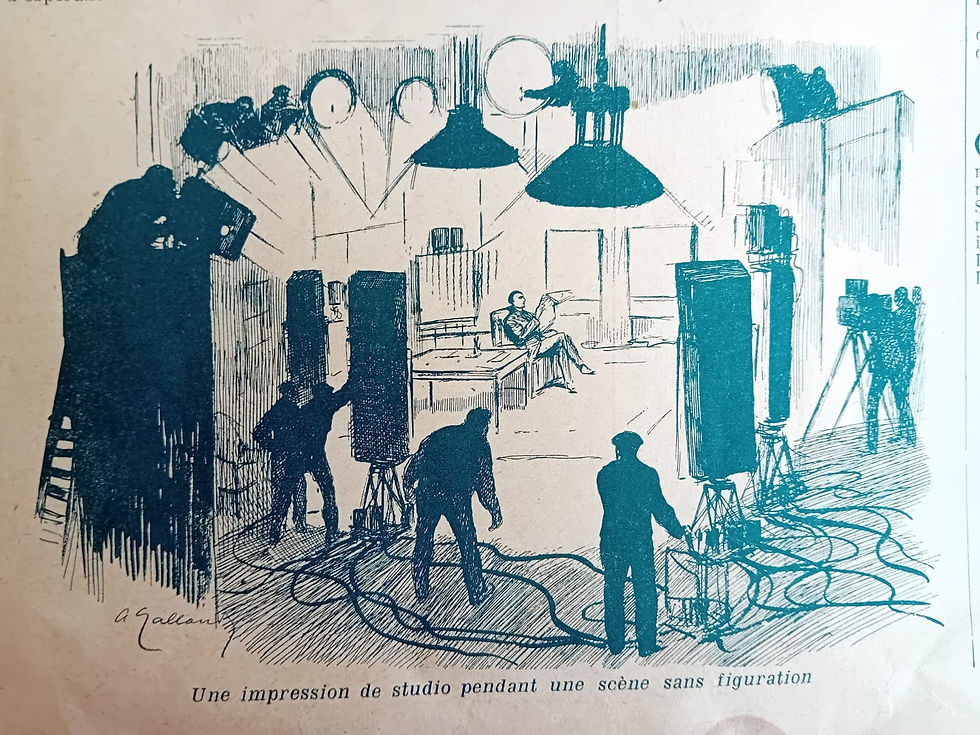

In Cannes, a working cut of the project, “Liberators of Shadows,” was screened as part of the Cannes Film Festival program for residents, “Private Cinema for Great Films.” The project explores the lives of extras who worked on French film sets in the 1920s and 1930s. The film is the result of historical research based on newsreels, feature films from that period, and newspaper photographs.

The film is a paradoxical collage of newsreels, photographs, and texts projected on the walls of cities where refugee-actors arrived from countries plunged into horrors of revolutions and ensuing regimes. This is a virtuoso work by Mary Drubezkaya, Aleksandr Kiselev, and Sergey Garjkavyy.

Chapter 1 – Refugees’ Dreams

In June 1917, on the rocky shore of the Black Sea, cinematographer, Yevgeny Bauer, destined to become a great reformer of cinematic language, slipped and fell, quite by accident. It happened one late evening, during dinner with friends—members of his film crew. Dizzy from cool white wine, fragrant of daffodils, they all had their suitcases packed: the real flight and emigration would begin that morning.

Numerous film crews from blood-soaked Muscovy, Riga, and Prague, in their entirety or in disarray, were making their way to Berlin and Paris. They included stars, past and future. But our research focuses on those who began earning their keep as extras on Parisian and Berlin sets.

They were lost and bemused. As it’ll be a bit more than 1 hundred years again.

“To tell the truth, cinema was the last thing on my mind while traveling as an emigrant from the Caucasus to Europe. My modest dream was to draw postcards and sell them. Instead, I ended up with the Moscow Art Theater’s Prague troupe in the film ‘Raskol’nikov’ . . . I vividly remember making my first film set. The director said, ‘The table is too straight. . .’ So I made it crooked.” These are the memoirs of artist and set designer, Andrei Andreyev. The film became one of the masterpieces of surrealism in cinema. It established the idea of curved space. The movie screen, as usual, became a reflection of reality—hundreds of thousands of refugees found themselves in a curved space-time at that time.

In Paris and Nice, thousands of refugees worked as film extras. “Sellers of their own shadows,” as one of Nabokov’s characters called them.

Chapter 2. Newspaper.

From the newspaper “Kino” (“Cinema”), July 13, 1923.

An émigré extra. He doesn’t resemble the locals willing to dress up as anything. No, every émigré in the region—despite the daily hardships for a crust of bread—has not squandered the noble upbringing: has not forgotten how to bow to kiss a lady’s hand, how to glide through a glittering ballroom, how to recline in a gilded armchair. Donning a general’s uniform—his own with his own medals—he trembles inside. . . Willpower of cinema returns him to his former self.

Pleased, the director exclaims, “ça va”—unaware that the crowd of attentive, sensitive people is reliving a fleeting dream of their distant past, a dream for which it is so painful to receive the meager fee from the box office. . . Nonetheless, it is this fee that sustains them right now.

Newspaper. September 13, 2022. 9 am.

Preparations are underway for the ball. Rumors of breakfast and earning some cash spread quickly.

From an article titled “Necessity Leaps”:

“Tardiness is unacceptable. Clothes must be impeccably cleaned and ironed. Being caught looking sloppy means not only losing your income this time, but also losing hope of any income forever!”

Newspaper. September 21, 1923:

“Refugees have common dreams: returning home, a moment of rest, admiring their homelands, and then plunging into the horror of memories, the appearance of soldiers, and then, depending on the level of nervousness—arrest and awakening.” Dreams of their own and others’ misfortunes.

The filmmakers start with these opening shots:

A bookcase on a street in Cannes, perhaps near the Castle? Zephyrs of texts waft by every time you pass. Sometimes it holds an encyclopedia of potato dishes from 1972. Other times—splendid library volumes. Purple-inked signature reveals the owner, whose basement cleaning landed the books here. Oh, the voices, the sounds, the wind with the dust of letters and punctuation marks, the haze of periods and commas, the cloud of paragraphs.

Suddenly, we got lucky and found a stack of newspapers, "Cineglaz" (“Cine-eye,” i.e., cinema lens), from 1921, 1923, 1924. Finders keepers!

There, among these newspapers, we came across articles about émigré film extras, and our research, which had initially sparked as an abstract idea, became reality.

Then we went to Marseille to film the port where ships had arrived carrying immigrants who, by the will of fate and chance, would work as extras on various film sets. We went to Paris to the Cinémathèque, where complete archives of film newspapers could be found. We went to Nice to see an old studio.

For my friend, this is partly a personal story—a hundred years ago, his family was split in two: half remained behind the regime’s fortifications, the other half made it to France via Finland.

And here we are, taking a bus to the port of Marseille. My friend’s father worked in Moscow as a circus carpet clown—even before World War II. For him, the idea of escape was but a hypnotizing mirage. . . Meanwhile, his older sister, an actress, wandered around film sets in Latvia, France, and Germany. . .

We are film archivists by profession, hence our fascination with the magic of non-existent footage. A brief digression about research in film archives: dusty rays of light penetrate the film vault, metal boxes of reels rest on wooden shelves, and, in the nook by the window, there is a table with a teapot and sandwiches, where film-distribution goddesses, Valya and Olya, guffaw. Endlessly, we stare at frames on the editing table of mid-1950s design. We search for something irreplaceably concrete. Once we came across the striking images of refugees—from in the 1920s and the 1940s—scurrying about, looking pitiful, getting their documents straightened out. . .

The film’s tempo is set by the swaying of emerald waves in Marseille, back and forth. Back to the 1920s. Forth to the streets of Marseille, Nice, Cannes, Paris, Berlin. Back to excerpts from the 1920s films. Forth to the newspaper department of the Cinémathèque Française in Paris. Back to historical newsreel footage. Forth to the editing table, where we watch 35 mm film reels, trying to find our heroes. The voices are from newspaper texts from 1920-1931. The wording sometimes seems naive. Phrase constructions are largely old-fashioned. Note that the language used to talk about cinema was only just developing back then. For example, instead of the verb “shoot” (to shoot a film), the verb “spin” was used: to spin meant to make a film. Who else besides us contemplates film extras from a century ago? . . .

Kaleidoscopes and puzzles are more intriguing than a finished film—they offer more dimensions, possibilities, imagination. Everyday life of extras is more interesting to us than that of actors. The nature of their work leaves the extras suspended between reality and screenplay. They don’t engage in the technique of transformation. They enter the door of History and then exit—sometimes slamming that door, sometimes closing it softly. The 1920s emigrant extras are a special community. Nervous. With a piercing sense of History. Continuing the door metaphor: filming traps them in History’s doorframes and portals where their past looms in the corners. It’s a unique community—if a community at all—comprising many disparate unhappy people. Disheartened not by nature, but by fate, they came together against their will. Nabokov’s “nameless shadows, unleashed upon the world.” Yet sometimes they feel happy and become real gamblers! They wholeheartedly hope for good luck.

The film will take its final form within the next six months, and we will see the new version.

Comments